4.2 – the idiom of the guitar

SARAIVA

The figure of the composer-guitar-player pervades the history of the European concert music, and articulates with the popular music; thus getting to different resultants and a wide range of solutions.

In a general view, a fluent guitar composition will only come to life by the hands of whoever plays the instrument.

Inside the Brazilian song tradition, the figure of the “cantautor” (singer and author) integrates the act of composing with playing.

That is, in both cases whoever composes is who plays it.

How do you see this coexistence between composing and playing?

ASSAD

I partially agree with what you’re saying.

This is a recurrent discussion I have had with my colleagues in San Francisco, where I’ve been teaching for 5 years.

They are people who believe that you don’t need to play an instrument in order to write for it.

There is some reasoning in this argument, because if you start analyzing, great guitar pieces from the twentieth century were written by composers who don’t play the instrument.

To start with Nocturne by Benjamin Britten, a composer who probably has never touched the instrument and left us this wonderful guitar piece.

When you think of Joaquim Rodrigo, who wrote fantastic things for the instrument, or Castelnuevo Tedesco, who wrote far more musical notes than the guitar could handle.

That does not prevent us from adapting, keeping the inversions of chords that he wanted and ending up making our version of the music.

When a person doesn’t play the guitar is capable of imagining things that the guitar-player would have never imagined – that is possible. [i]

On the other hand, it is also possible that the person imagines things because he/she plays the instrument – such is the case of Villa-Lobos who changed the history of how to write for the guitar using its natural relations.

SARAIVA

Idiomatic

A game then is established between the resources that are inherent to the instrument’s idiom, commonly called “idiomatic” or “guitaristic”, and that thing that the composer, who does not play the guitar, is capable of imagining and that the guitar-player would not have imagined. [i]

The musical example executed by Guinga that follows presents the range of his musical thinking. Guinga explores, in the field of the song, the interplay of two-way impulses that are characteristic to the polarity between what is “guitaristic” and what is “marvelous because it is not guitaristic”.

GUINGA

00:00 but there is something misleading in here

But there is something misleading in here, [i]

Chico Buarque besides being a great lyricist is a great guitar-player.

He plays the guitar his way and nobody can imitate him.

I have never seen in popular music anyone inverting chords like he does.

His music has an incomparable architecture,

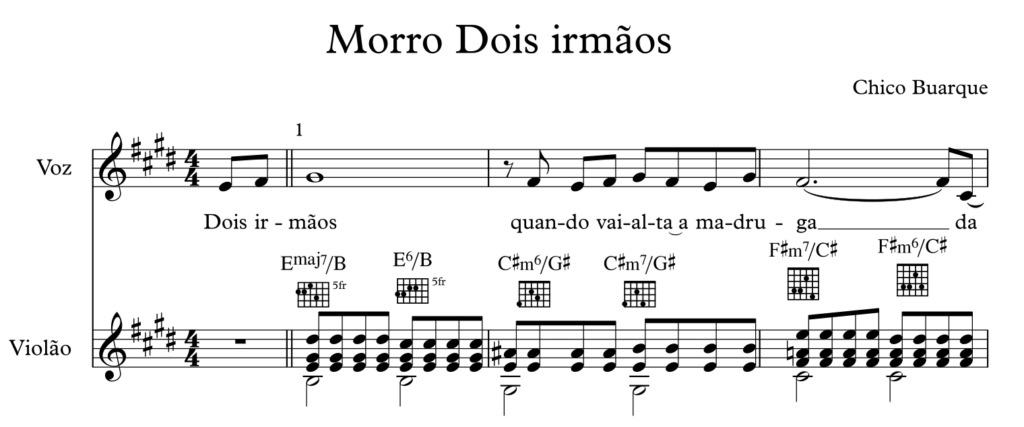

for example, “Dois Irmãos”

[ he plays the complete music that evolves from the following part]

00:40 Morro Dois Irmãos (Chico Buarque)

01:40 note E at the end

02:09 wonderful because it is not guitaristic

03:08 which guitar-player would compose anything like that?

In a crossing movement, which cuts through the square presented at the opening of this chapter, Chico Buarque, a “songwriter” who “has never considered himself a guitar-player”, gives a good use to the years spent at the foot of Jobim’s piano developing a structure that a scholar guitar-player would hardly have imagined, and Sérgio Assad, guitar-player – composer of sound formal musical education, holds firmly on what he feels as essential to the song communicability without failing to give musical priority to what “is going on behind the melody”.

ASSAD

00:00 in a good song the fewer notes the better [i]

In a good song the fewer notes you have, the better.

SARAIVA

Better chance to say, isn’t it?

ASSAD

Exactly

SARAIVA

On the other hand, there is this sensation of a musician facing a song

Despite the fact that many times the lyric has this main role,

and it is not even the case to measure this relation exactly

but for us who are musicians…

ASSAD

You are concerned with other elements, such as harmony.

I think that the first thing you listen to, in my case at least, is what is going on behind

I want to listen to the arrangement that was made, the solos,

what has been done as coating for all of that.

But at the same time I believe that simultaneously – this happens to me, a person

who doesn’t pay attention to the lyric – I have the impression that the lyric

is given presence because some interpreter has sung it in its full meaning.

Resuming the universe of the concert guitar, we give continuity to Sérgio Assad’s reasoning that grants depth to his vision on the playing-composing polarity by means of classifying the repertoire according to the relation between composers and the guitar.

ASSAD

01:22 great part of the guitar repertoire was written by guitar-players

02:05 the twentieth century – the figure of the composer apart from the instrument

02:35 the strand of guitar-players who make arrangements

02:47 these three things

Then there are these three things:

1 – music written by guitar-players

2 – music arranged by guitar-players

3 – music written by composers who have been increasingly getting interested in unraveling the potentialities of the instrument.

-

LINK with the idea “in some of my partnerships with Baden, I helped to compose parts of the melodies”, presented in – 5.5 – “Boi de Mamão” – in the statement of P.C.Pinheiro.

-

LINK with the phrase presented above in the statement of Sérgio Assad: “When the person does not play the guitar is capable of imagining things that the guitar-player would have never imagined – that is possible.”

-

At this point Guinga, as far as I see, finally answers my question: “Cartola and Nelson Cavaquinho, for example, who played the guitar, would get to modulations and relations between tonalities that were already different. How do you see it?” — directed to him during his interview, presented in 3.5 – it seems easy but it is impossible .

-

LINK with the same idea presented in – 6.3 – an old issue .