6.2 – the “Jongo” of Bellinati and the “Jongo of Tamandaré”

Guitar-player Paulo Bellinati composed Jongo, one of the most performed guitar pieces in the field that lies between the popular guitar and the concert guitar. [i]

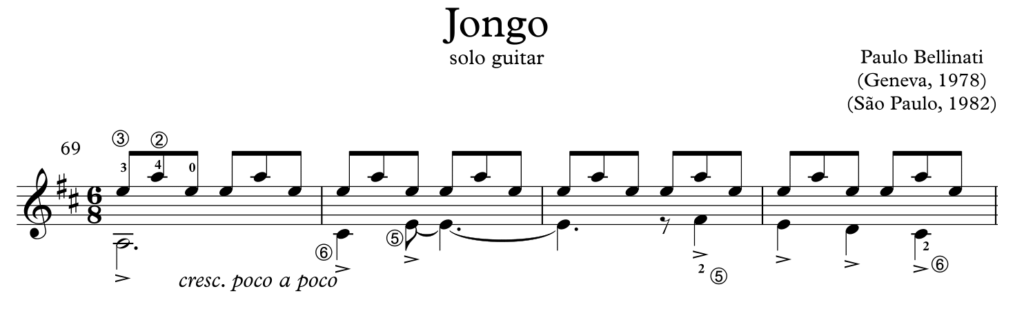

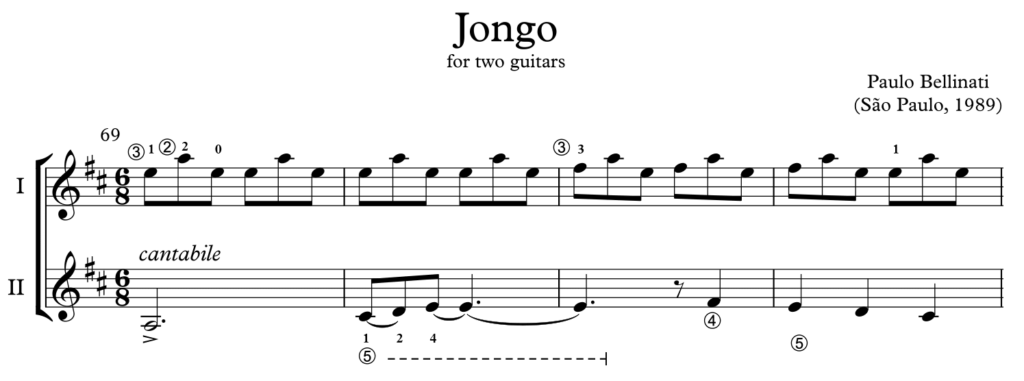

Above, four bars are presented in the solo version, and below, the same part is presented in the duo version. [i] [i]

SARAIVA

I admire the way you can write the same music for different formations.

‘Jongo’, your best known piece, exists for solo guitar, duo guitar, and also for other formations.

Was it born as a solo?

BELLINATI

No, actually not. It was for an instrumental group.

SARAIVA

Like that with a saxophone, in the format of the Pau Brasil?

Then it was like a song, a theme?

BELLINATI

Jongo started being gestated for that instrumental group,

when I was living in Switzerland.

It was a piece that I had been composing in which the guitar would have an important role.

That group by the way could never play it.

The solo version was written when I returned to Brazil,

at the time that I was doing the transcription of Garoto,

that’s why it might have had some influence.

It’s only then that I elaborated the solo version, [i]

and the ‘Pau Brasil’ records the version in group.

Those are pieces that took years to be ready.

A piece of music of such magnitude and with that quantity of information

takes years to gain the format it has.

SARAIVA

It was a process…

BELLINATI

It is a process. A process of evolution in the pieces of music.

I started understanding myself in the world as a Brazilian guitar-player.

This long life and learning process that mold the composer.

You become a composer when you have stored a great amount of internal material

and from that accumulation you can say something original.

It took me a long time to become a composer.

According to Bellinati, the “evolution” process of pieces of music interlaces with the forging of a composer. In this process the “internal material” accumulated as a guitar-player has an important role, while the maturing time is respected as a determinant factor in the development of both the composer and the work.

Tom Jobim appears again as a reference – now connected to the time dedicated to the continuous formation of the author and the composition of more elaborated songs.

BELLINATI

I think that the work of Jobim would have never existed without all the study that he did as an arranger. [i]

He kept the preludes of Chopin on his piano because he dedicated himself to reading them every day.

Thus, he was in contact with the wealth left by the impressionists at the end of Romanticism.

It is unlikely to imagine that a composition like ‘Luiza’ is simply intuitive.

I think that ‘Luiza’, ‘Choro Bandido’, ‘Beatriz’

only came to existence because someone who had studied a lot and had a great deal of musical “knowledge” created it.

Because it is impossible for this kind of harmonic-melodic density to appear instantaneously.

In the special case of ‘Luiza’, Jobim dedicated a long time to compose it.

SARAIVA

Elaborate…

BELLINATI

He spent months and months elaborating, looking for the melodic lines, solutions.

A very rich piece of music – a master piece – that doesn’t come out overnight.

00:00 Jongo (Paulo Bellinati)

Herein, we present a recording of Jongo (Paulo Bellinati) by Duo Saraiva-Murray with special participation of the author, in May 2016 (thus, after the end of the dissertation) at the release of CD Galope Duo Saraiva-Murray, produced by Paulo Bellinati.

This recording approaches the universe of origin by means of tuning a melody that comes in fact from the repertoire of “Batuque” de Tietê/Capivari(SP) – a gender akin to Jongo – and which inspired the piece written by Bellinati.

04:07 Namoro c’uma moça

The girl I date

isn’t white isn’t ugly

The girl I date

isn’t white isn’t ugly

White kerchief on the head

two beads on the ear

strikes midnight the earring shines

strikes midnight the earring shines [i]

It seems that time appears in two aspects to be considered herein: the time that a composer takes to get constituted facing the universe(s) in which he is inserted; and the time that is taken to compose a new work. Both periods are relative and dependent on a large number of variables. Despite that, we propose once again to work on the polarity determined by the difference between the abilities of the composer and of the songwriter.

The composer is expected to have a formal education, learning composition techniques that are current in the history of concert repertoire, which with practice will enable the writing of pieces without spending a very long period of time. The songwriter’s process, on the other hand, is explosive enabling the instantaneous birth of a long-lasting song that many times lullabies the dawn of the night during which it was composed. [i]

An exception that helps to confirm this rule is Dorival Caymmi. According to Sérgio Cabral, “Caymmi takes long to compose music, some friends say, […] but when he concludes a piece of work the Brazilian music gets richer”. [i] In other words, if Caymmi took long, it was related to the short time that a songwriter generally spends to compose a song in Brazil. Caymmi himself is one of the authors that inaugurated the natural connection between the universe of the urban popular song [i] – which feeds directly on the world music, including the erudite – and the Brazilian folk music. [i]

P.C. PINHEIRO

You’ve already seen it closely because ‘A Barca’ has been to such specific places searching for these things.

Then you’ve got everything,

dance,

feeling,

emotion, fright,

the amazement at creating.

There’s everything in those pieces of music.

The creation force of the moment shows itself as one of the indispensable vertices in the study of the polarity between the “fixed” and the “flexible”.

-

The piece was recorded – in the duo version – even by John Williams, one of the concert guitar icons of all times. Available below and also on www.violao-cancao.com/referencias

-

It is notable that the duo version resorts to greater mechanic freedom to highlight the sense of “cantabile” in the part. That allows for the insertion of a note explicated by the legato that takes place on the fifth string of the second guitar in the duo version. It is a note that, even belonging to the principal melody of the part – which would likely have lyric in an eventual “song version” of the piece – , in the solo version is omitted due to the instrument’s digitation “limit” that simultaneously supports the accompaniment fingering that takes place in the raw strings. Such “freedom”, generated by dismembering the solo piece allows the first guitar as well to have greater expressivity of the part, which thus gains descendent directionality (indicated by the arrow) by the insertion of an F# executed by the finger on the third string (that follows D in bar 73 of the original score).

-

LINK with the idea of “guitar limits” presented in – 1.1 – a guitar that sings – in the statement of Sérgio Assad.

-

LINK with the central idea presented in 6.3 – an old problem.

-

LINK with the idea “that is a form to enrich, which must have been very significant for him (Jobim)”, presented in – 2 – searching for the other – in the statement of João Bosco.

-

“The song comes out immediately, and that’s what matters. Naturality, spontaneity, and instantaneity are precious values to the songwriter. The quickness and efficiency of rescuing experience cause the inspirational effect”. Luiz Tatit in O cancionista, São Paulo: Edusp, 1996, p. 20.

-

Sérgio Cabral, “O ritmo de Caymmi”, in: Dorival Caymmi, Dorival Caymmi: Songbook, Rio de Janeiro: Lumiar, 1994, p.16.

-

“a person who has changed my life was Dorival Caymmi” – states João Bosco in part of his statement presented in – 1.2 – a guitar that meshes with the song .

-

“Whether linked or not with newspaper companies, the specialist – called “critic” – handles the knowledge from which a divulgation process about the composer or artist is set up. It is the same role as that of the folklorist – now on industrial basis. The old “science” of folklore is established in the division between popular culture and erudite culture. It is an artificial cut because in the popular (connoting simplicity, easiness, naivety) the erudite (connoting complication and complexity) is also present. However, this division is necessary for the erudite folklorist to establish the discourse.” (Muniz Sodré, Samba, o dono do corpo, Rio de Janeiro: Mauad, 1998, p. 53)

-

It is worth mentioning that in the book the conclusion of this chapter evolves from a tune composed by Totonho do Jongo de Tamandaré, in which the 6×8 bar is preponderant. Like the Jongo by Bellinati, and differently from Jongo da Serrinha presented in the previous chapter by João Bosco.