6.3 – an old problem

SARAIVA

I’ve recently had a significant experience — it was to rewrite that first partnership of ours, “Incerteza”.

TATIT

That is an old song; it was in your first instrumental album, wasn’t it?

SARAIVA

That’s it – the first I gave you.

TATIT

I remember.

SARAIVA

Released in 99.

And I didn’t write it at the time because of this likelihood of mobility,

which is inherent to the song.

And now, in the post-graduation course that studies the so-called “erudite music”,

I managed to get to a score for a guitar quartet that has come up to my expectation.

That of course means that there is likely to be a new version.

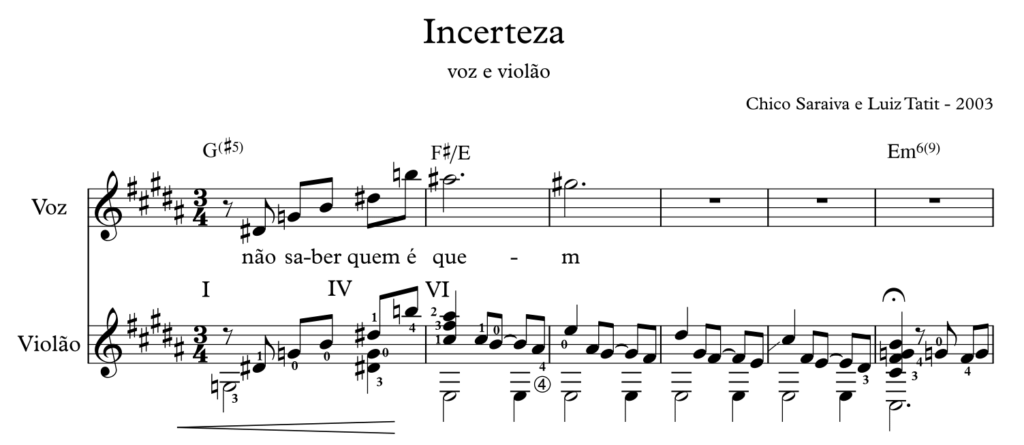

Following, we present scores of one of Incerteza’s musical passages for different formations to show the course taken by the composition over the time. The first instrumental version [i] ; the second, the recorded version with guitar and voice, sung by Simone Guimarães with lyric by Luiz Tatit [i] ; and the third, a version recorded by the guitars of Quarteto Tau [i].

00:00 Melodia para a incerteza | Álbum Água

00:00 Incerteza | Álbum Trégua

00:00 Melodia para a incerteza | Álbum Cordas Brasileiras

TATIT

Jobim did that over the time,

he closed versions, and every time he would play them in a little different way. [i]

SARAIVA

Then he was a song-writer, wasn’t he?

Leaving it flexible.

TATIT

Jobim is typically like that.

The song-writer does not worry about the details of notes – the utmost interest is in the complete inflection.

That’s why there are songs whose finalization is descendent,

and the person ends it up ascendant, which in erudite music is inconceivable.

SARAIVA

In the sheet music, the note that holds is the one that is written.

TATIT

That doesn’t exist in the song.

The song keeps being made by interpretations.

The song keeps changing, and even the author when recording it again,

does it in a way that sounds like a version already listened to.

That’s what makes it provoking and at the same time different from the thought that was written down.

SARAIVA

It is another thought.

TATIT

It is another thing.

SARAIVA

Then you realize…

I’m trying to move between these two areas.

That consists in a hard and ancient counterposition as far as I can suppose.

I’m talking about something that is very, very old. [i]

TATIT

Yes, something that has never been settled.

When we talk about the difference between written music and song-vocationed music,

normally the idea is that it is something else, some other object.

The song with vocation is thought to be necessarily slower,

so that the inflections become more comfortable.

Indeed, the term song in general leads the musician to some understanding that coincides with what Tatit has placed above, as it can be confirmed, for example, by the statement “the best songs in reality have few notes and more breathing,” registered in the interview with Sérgio Assad for this dissertation. [i]

TATIT

Dynamic song, however,

is a song that ends up inclusively being much weirder than being finalized,

because it is based on the speech instability rather than on some comfort for performing inflections.

Thus, the problem is ancient, but we don’t know yet what we are talking about.

The good side of academic life is that permanence in the area is long and then you can discuss it several times.

The note in the third bar of Incerteza’s voice and guitar transcription presented in the sheet music happened spontaneously in Simone Guimarães’s interpretation. The note appeared only in the take chosen for the CD, for in the other takes, the singer kept the A sharp, of the original finalization of the phrase. [i]

(as indicated in the sheet music).

Such flexibility is natural in the song world, although some determined strands and popular authors try as much as possible to avoid this kind of flexibilization of the melody. On the other hand, in the world of erudite music, either in the song (Lied) or in instrumental music, the flexibilization of the heights signaled on the sheet music, including those that constitute the melody, tend to sound like a resource out of context.

The complexity of this “ancient problem” demands, in my opinion, considerations that come from the most varied points of view. Because the referred “instability” of the speech, a hint that reveals in-depth Tatit’s subtle perception, interacts with other dimensions that also deal with the stable/instable duality from other parameters.

The speech has always been related with rhythmic aspects, because in Africa, and consequently in Brazil, the vocal gesture does not distance from the musical g

“reference rhythmic motifs”, which act in the “basis” of the musical fabric, are orally transmitted using native inflective resources of the voice that result in a sort of vocal percussion – by the way as it has appeared so many times during our musical dialogues [i]. It is about structural rhythmic phrases that directly address the stable/instable relation resulting in countless possibilities of rhythmic/vocal articulation that in the song context reach the word.

Another dimension, the “instability of the speech”, is directly related to our consideration. Viewed by Tatit as “dynamic song”, it leads to a route connected not with the axis of rhythmic durations but rather with the axis of heights, which conducts us to the harmonic-melodic instrument. In this realm, the piano offers countless possibilities, and the guitar a “limit” that endows it with an “essential” character that is closely linked with the song. The fact is that in the fertile game between voice and “active instrument in the melodic search”, the instrument both proposes ways to the voice, through which it could move, and mirrors the voice in an attempt to imitate it [i] – a process that is quite evident in the recent works of Chico Buarque, for example, in Bolero Blues (CD “Carioca” – 2006), which according to Chico himself is “impossible to sing” [i] , or in Rubato (CD “Chico” – 2011).

Both songs are melodies composed by instrumentalist Jorge Helder which, with lyrics and filters experienced by Chico Buarque in song [i], reveal the frail equilibrium between the vocal gesture and the instrumental gesture – in compatibility with the thread that orients this research and dialogs with the concept of musical gesture.

-

CD “Água” (Cântaro – 1999/MCD – 2003) recorded in partnership with Eduardo Ribeiro (drums) and José Nigro (bass). Available at http://chicosaraiva.com/albuns/agua/.

-

CD “Trégua” (Biscoito Fino – 2003) Available at http://chicosaraiva.com/albuns/tregua/.

- CD “Cordas Brasileiras” – Quarteto Tau – (Delira-2011)

-

LINK with the idea “a process of evolution in the pieces of music” presented in – 6.2 – the “Jongo” of Bellinati and the “Jongo do Tamandaré” – in the statement of Bellinati.

-

canto dessa música.” Roy Bennett, Uma breve história da música, Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar, 1986, p. 13.

Historically, the rhythmic of the text when it is sung has always been determined by the word. And, exactly there – in the main spring of the European musical writing tradition – , the notation was limited to the determination of the heights: “In its first phase, the religious music known as plainsong (plainchant) had no accompaniment. It consisted in melodies that flowed freely, almost always keeping itself within an eighth interval, and developing, preferably, through intervals of a tune. The rhythms are irregular, coming in a free way, according to the accentuation of words and the natural rhythm of the Latin language, which is the singing basis of this kind of music.” Roy Bennett, A brief history of music, Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Sahar. 1986. P.13.

-

LINK with the idea “the best ones have few notes” found in chapter – 3.1 – the non song.

-

LINK with video Paulinho da Viola talking about a song by Lupicinio

-

“The rhythmic motifs for reference are transmitted from teacher to student through mnemonic syllables or phrases” (KUBIK, 1981, p.93).

-

LINK with Edu Lobo’s idea presented on p.212: “When you compose on the piano, […] you make the chord and sing a note, but the finger chooses another way, and the brain registers and chooses what it prefers”.

-

Chico Buarque introducing the lyric to Jorge Helder, partner and bassist in his band.

-

Chico Saraiva’s remark in – 4.2 – the idiom of the guitar – “Chico Buarque gives a good use to the years spent at the foot of Jobim’s piano to develop a structure that a scholar guitar-player would hardly have imagined”