3.1 – not canção

SARAIVA

00:00 the song and the voice

My sensation is that when we are inventing music

there are things that come more via voice

and others come from the guitar.

GUINGA

00:00 always by means of the voice

No, the song always comes via voice.

SARAIVA

Always via voice?

GUINGA

With me it always happens by means of the voice.

When I make music without singing, I already know that that is music for the guitar.

But I am a song composer; I am not a guitar music composer.

I’ve spent my life with a guitar in my hand, if you make accounts I have really some —a considerable number of pieces composed for the guitar, but I am a song composer.

Please… this is the great pride in my life.

Trying to be a good song composer,

I’ve spent my entire life trying this.

01:02 the non-song?

SARAIVA

And how do you view the influence that the guitar gestures

have in the melodic course of a song?

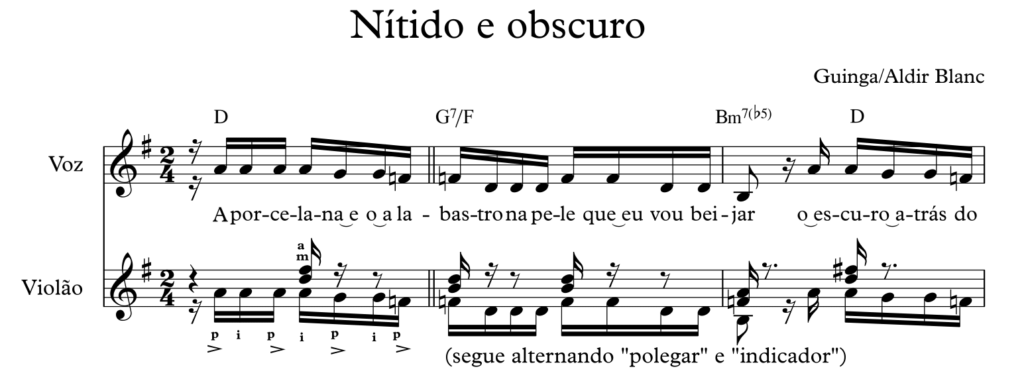

I play the initial part of Nítido e obscuro – a baião (Northeast Brazilian rhythm) [i] , with vocal inflection emphasizing articulations that, to some extent, are present in the digitations marks of the right hand, shown in the score that we reproduce in the sequence:

GUINGA

That is some music that had no pretension to be a song.

But it has come out all right. If the person can sing it, it sounds very good!

But it is not like doing

[plays]

01:25 two songs: Senhorinha (Guinga/P.C. Pinheiro) and Lendas brasileiras (Guinga/A. Blanc)

In order to consider my remark about this “music that had no pretension to be a song”, Guinga plays two of his pieces that represent the other extreme of a polarity that is herein revealed. Slow tempo songs and with melodic movements based on grouped degrees punctuated by melodic leaps in consonant intervals [i] , which are played one after the other.

GUINGA

02:15 I have never made music without the guitar in my hand

The talk with Sérgio Assad takes us back to Garoto, and then to Pixinguinha:

SARAIVA

00:00 Bellinati: everything that Garoto did is classified as song [i]

ASSAD

01:39 when there are too many musical notes it becomes difficult to convey the message in the form of a song

02:44 that is arguable…

03:00 there is this tradition of music that is born instrumental but has this “song background”

03:40 the best songs have few notes [i]

04:30 for the musician, “song” means something more decelerating

Both in the formulation of Assad and in the two examples chosen by Guinga to represent his authorial interest intrinsically connected to the voice, the association of the term “song” with music of slow nature is construed. The specific music that reaches “the greater breadth of expression” and a wished “abandonment to melody” when it uses “few notes and more breathing” in order to facilitate the “placement of the message that the text wants to convey” [i]

In the midst of this context, the lyricist’s view presents itself as an important parameter that in some cases can even select inside the composer-instrumentalist’s piece the melodies that reveal, through its melodic contour, the song vocation. P.C.Pinheiro has converted countless instrumental themes – some already consecrated in this format even before being given lyric – in songs.

P.C. PINHEIRO

00:00 Amazon River with Dori Caymmi

00:44 Ingênuo with Pixinguinha

00:58 music tells me [i]

Inside this “tradition of music that is born to be instrumental” with “a song background” is still worth mentioning Carinhoso, composed in 1916 by Pixinguinha. Fundamental composition in the Brazilian music, which, born instrumental and having had the lyric written later by João de Barro, has been heartily sung by audiences for decades. That fact is evidence of the fertility that the melodic design of instrumental origin [i] has supplied the song in Brazil since its beginning.

Delineated by the “musician”, the melodic design interweaves with poetry and the “songwriter’s” listening, represented by the figure of the poet. Poet who, in turn, feels that “instrumental origin” of the melodic material as a predicate that tends to the strictly “musical” field — which leads the poet to keep, most of the time, a safe distance from infinite musical possibilities that the instrument provides, dimension that may represent a threat to the nature and to the “intoning” fluency that are intrinsic to the melody of the song. [i]

-

Excerpt of a score in the A Música de Guinga (Guinga’s music), p. 111, Ed. Gryphus. 2003.

-

Andamento (tempo) of an opposite character to Nítido e Obscuro and interval dynamics significantly different from that realized in songs like Para quem quiser me visitor – presented in the previous chapter – that bases its melodic course on dissonant intervals.

-

LINK with the idea “Garoto was a composer who made songs on the guitar” in – 1.1 – a guitar that sings – in the statement of Paulo Bellinati.

-

LINK with the same phrase written in 6.3 – an old issue.

-

5. LINK with the idea “dynamic song” presented in – 6.3 – an old issue – in the statement of Luiz Tatit;

-

LINK with the idea “there are several situations that mold this moment” presented in – 7 – inspiration – in the statement of João Bosco.

-

In this case, born not from a melodic-harmonic instrument, but from a wind instrument, which we are used to linking more directly with melodic expressiveness.

-

LINK with the idea “And it is not like that. Sometimes tapping out on a table, and afterwards goes to the guitar” – presented in – 3.3 – the song without the guitar – in the statement of P.C. Pinheiro