4.1 – guitar-piano

SARAIVA

00:00 integrated voice and guitar tradition

There seems to be a tradition of integrated “voice and guitar” in the Brazilian song, resulting in a part of the guitar that would almost be an “accompanying piece”.

MARCO PEREIRA

00:50 Berlioz’s orchestration treatise

02:15 the guitar is a small orchestra

Then it is as if it were the whole band.

You listen to a guy like João Bosco,

when he presents just the voice and the guitar,

his guitar sounds like a band, there’s everything in it: [i]

In the statement of Sérgio Assad transcribed below, he shows that the formal writing resources – specific to those who “studied in a music school” – equilibrate with the author’s long-lasting practice in composing popular songs.

ASSAD

00:00 somewhat contrapuntal harmony

Whenever I write a song, the melodic part is really very important,

but it’s my style to make a somewhat contrapuntal harmony,

which results from the fact that I have attended a music school.

Then I start inserting those resources in my songs.

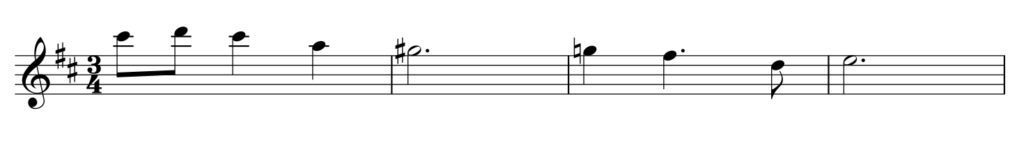

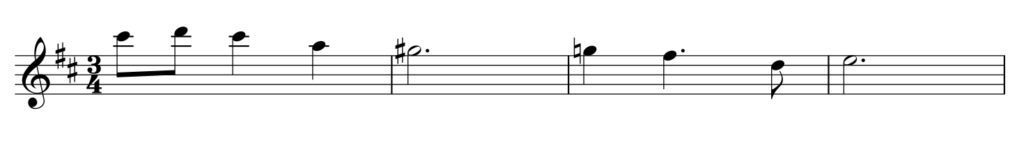

If I play this melody that I wrote several years ago and there are many people playing it

[he plays the melody]

I’m going to insert, for instance, harmony

[he plays the harmonized melody]

now I can play

[he plays it with harmonization and second voice]

then you’re putting that second “layer”on, and the thing starts getting more interesting,

without missing the focus on the melodic line.

The things I do are all like that,

This same piece is like that

[plays]

The guitar somehow carries in itself these possibilities.

You can make so many different timbres …

This thing of being sort of an orchestral instrument

brings many possibilities, despite being very limited.

The constant fight with the guitar is this:

it’s an instrument that cannot do what the piano does,

but it has a very particular beauty that turns many people’s head.

Sometimes, someone appears doing just with a guitar what I found

difficult doing with two. Then I continue asking me, ‘what’s the limit to it?’

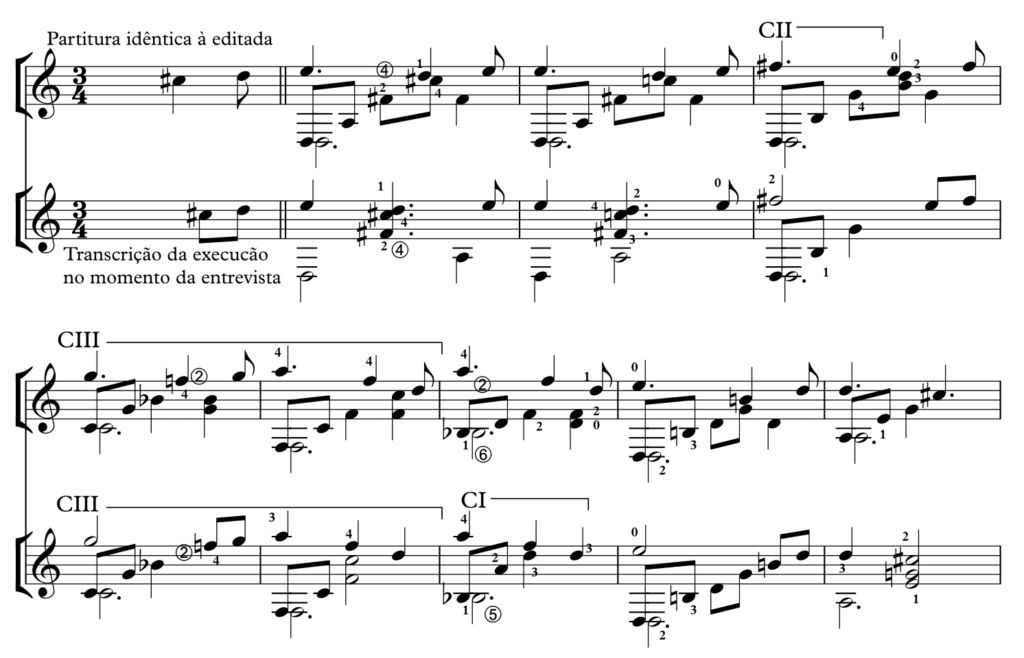

The differences noticed between the execution at the moment of the interview and the edited score of the piece lead us to present the musical content in the way it is shown above in order to facilitate the comparison. The top music notation contains the edited score [i] , and in the notation below is a transcription of how the piece was executed at the moment of the interview. Looking at this disposition of notations, it is possible to highlight the ways, even in the universe of written tradition totally linked to the concert music – means through which this piece is spread –, the compositional decisions [i] that have constituted the edited score may present a certain degree of mobility, at least when in the hands of the guitar-player/composer of the piece. This mobility very likely retraces the stages taken by the composition throughout the authorial process. [i]

ASSAD

02:40 the orchestral guitar

-

LINK with the idea “sounding like a band” that here is equivalent to what João Bosco calls “solo version” in the chapter – 4.5 – playing together;

LINK with the idea “sounding like group”, presented in – 4.4 – vigor and subtlety – in the statement of Sérgio Assad.

-

Cf. Sérgio Assad, Aquarelle, p. 12, Paris: Henry Lemoine Editions, 1992.

-

LINK with the idea “from the moment when you write it down on paper it starts being your intention” presented in – 6.4 – the moment of writing – in the statement of Sérgio Assad.

-

Thus, in the composition of the piece, we point out a process of sedimentation that may even legitimate a consequent deconstruction (or “misreading” – according to Sidney Molina’s thesis title – that reaches this degree of flexibility) in the hands of the guitar-player- interpreter who, going against the postulates of written tradition, risks giving an interpretation that dialogues with the score based on musical intention as comprehended by the interpreter.